Miart 2020

LANDING ON THE FUTURE OF THE 20th CENTURY

When utopia and dystopia become reality

Galleria Allegra Ravizza

From 11th to 13th September 2020

International Modern and Contemporary Art Fair

Galleria Allegra Ravizza is pleased to present for this specific edition of Miart 2020 a journey that leads us to the future as imagined in the last century, divided into three stages: take-off, flight, and landing.

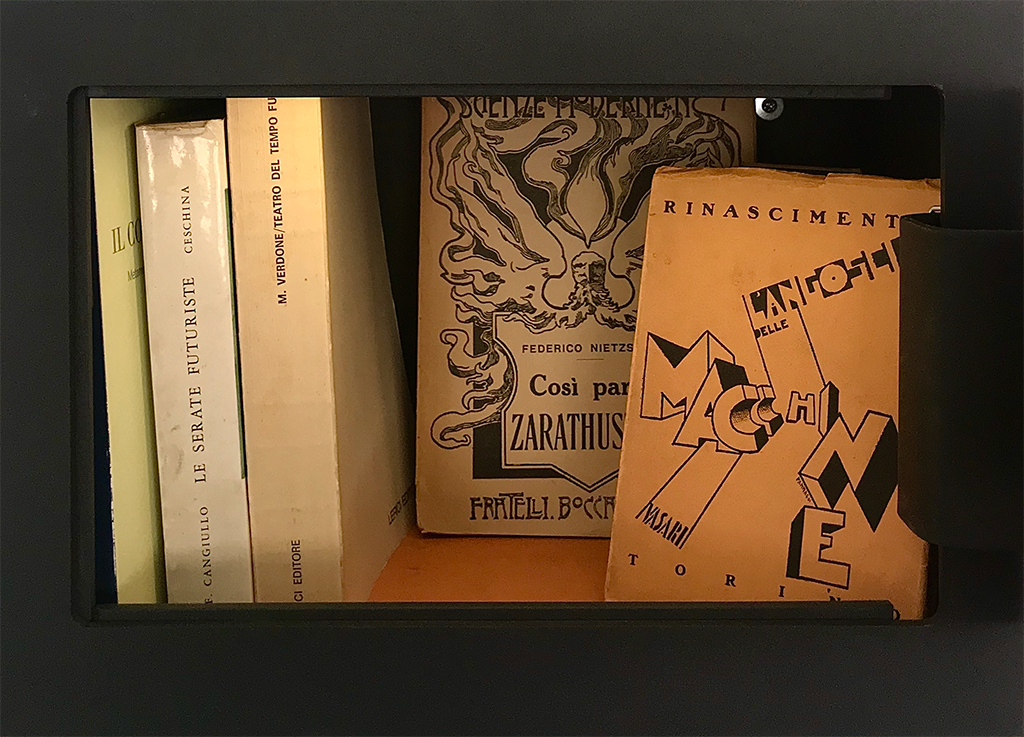

The TAKE-OFF with the famous 1921 book L’Angoscia delle Macchine by Ruggero Vasari, said to be the first real science fiction novel, set to music by the Futurist musician Silvio Mix, and which inspired the silent movie Metropolis, the masterpiece of Fritz Lang.

The FLIGHT in the metaphysical universe of the paintings by Bruno Contenotte, who collaborated with Stanley Kubrick on another masterpiece of the cinema, “2001: A Space Odyssey”, to finally arrive at Giulio Turcato’s LANDING on the surface of the moon.

TAKE OFF

In the 1920s, the young Italian composer Silvio Mix (Trieste, 1900- Gallarate, 1927), enrolled by Marinetti in the Futurist movement, wrote the seven “Commenti Sinfonici” for the drama by the Sicilian poet and painter Ruggero Vasari (Messina, 1898 – 1968) titled L’Angoscia delle Macchine (The Anxiety of Machines). Conceived in 1921 and finished in 1923, the work was defined by F.T. Marinetti as “one of the most important works that Futurism has given”[1] during a conference held at the Sorbonne, Paris, and which was translated into eight languages.

Vasari’s drama revisited the myth of the world of machines, much loved by Futurist aesthetics, in an openly polemical key, and recalled such typically Marinetti-like themes as conflict and contempt for women. The drama took place on a planet that was not clearly identified, the kingdom of machinery, where lived the protagonists Bacal, Singar, and Tochir, absolute lords in a society of compliant individuals condemned to be in the power of machines. A brain machine, directly linked to the three despots, gave orders and manoeuvred their will and that of the people of robots and of robotised men. The arrival of women, exiled from another planet, complicated the situation that precipitated towards a catastrophe: Tochir completely lost control of the brain machine and died, and in turn the machine became mad and in its destructive madness overwhelmed humanity and remained the sovereign of the planet.

The drama was set to music by the young Silvio Mix, who was then little more than twenty years old, and whose scores are to be found in the Commenti Sinfonici per L’Angoscia delle Macchine. It was Vasari himself who insisted on the importance of the music by Silvio Mix for the success of the play. The score consists of seven brief episodes: Prefonia, Commento I, Interludio (introducing the II act), Commento II (very short), Pantomima e Tragedia, Pantomima II and Finale. As in other scores by Mix, the musical writing violently dilates the dynamic space, sharply contrasting pianissimos and fortissimos, thus creating a climax within the piece, as happens in the third symphonic comment (Interludio). The score is interesting, furthermore, both for its use of instruments, such as sirens placed in two different points of the stage and used in the sixth symphonic comment, and for the use of a microtonal language[2].

The first performance of “L’Angoscia delle Macchine” took place in the “Art et Action” theatre in Paris on 27 April 1927. Having left for Paris in December 1926, Mix should have presided over the performance of the scene music he had composed for the drama. A sudden illness, however, forced him to return to Italy where he was taken to the Gallarate hospital where he died a few hours later. After his death it was decided to replace his symphonic comments with a piece of “noise polyphony” by Eduard Autant.

The original score was performed for the Italian Swiss radio service in 1989, curated by the musicologist Carlo Piccardi.

“L’Angoscia delle Macchine” was inspired by the silent film Metropolis, considered to be one of the masterpieces by the Austrian film maker Fritz Lang (Vienna, 1890 – Beverly Hills, 1976), presented for the very first time on 10 January 1927. Lang set his story in 2026 in a dystopian future where rich industrialists govern the city of Metropolis and oblige the proletariat, relegated underground, to incessant work. In fact there are numerous analogies with references to Vasari’s drama, but if this ends with the victory of the machines and an apocalypse caused by the love of machinery, in “Metropolis” machines are destroyed and humanity regains its independence and freedom.

FLIGHT

2001: A Space Odyssey, directed and produced by the American producer Stanley Kubrick (1928 – 1999) in1968 and the winner of an Oscar for special effects in the following year. A milestone in the history of cinema, “2001: A Space Odyssey”is also known for its soundtrack, among the most famous, consisting of pieces of music by classical and contemporary composers. Among them there towers over the others the German composer Richard Strauss (Munich, 1864 – Garmisch-Partenkirchen, 1949) with his symphonic poem “Thus Spoke Zarathustra”, composed in 1896 and inspired by the work of the same name by the poet-philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (Röcken, 1844- Weimar,1900) from whom he took the titles for various movements.

On the film there also worked the multifaceted and eclectic artist Bruno Contenotte (San Giorgio di Mantova, 1922 – Milan, 1992), who collaborated in the final scenes of Kubrick’s masterpiece. The artist’s experimental work was always concentrated on an analysis of the tangible reality of immaterial emptiness and cosmic energy, and created quant metaphysics in painting. Known and appreciated by the American producer, Contenotte collaborated on the film’s scenography by projecting the “Cosmic Sphere”, a series lasting about fifteen minutes in which colours, form, and light follow each other in the emptiness of space. The same figurations and colours are proposed again here in superimpositions of resin. The various resins of bright and fluorescent colours intersect on the canvases to create metaphysical figures that modify the canvas itself.

In 1984 the famous British group Queen launched their first single from the album “The Worker”with the title Radio Ga Ga, for which the video showed various excerpts from the film “Metropolis”.

In the same year the Italian discographer and composer Giorgio Moroder (Ortisei, 1940) worked on a new edition of Lang’s 1920 film. The restored negative, lasting only 87 minutes, proposed new and modern rock soundtrack. Among the music presented for the Moroder version, there also appears “Love Kills”, written and composed by Freddie Mercury together with Moroder. “Love Kills” appeared for the first time for the re-edition of the science fiction film on10 September 1984 as the only extract from the soundtrack.

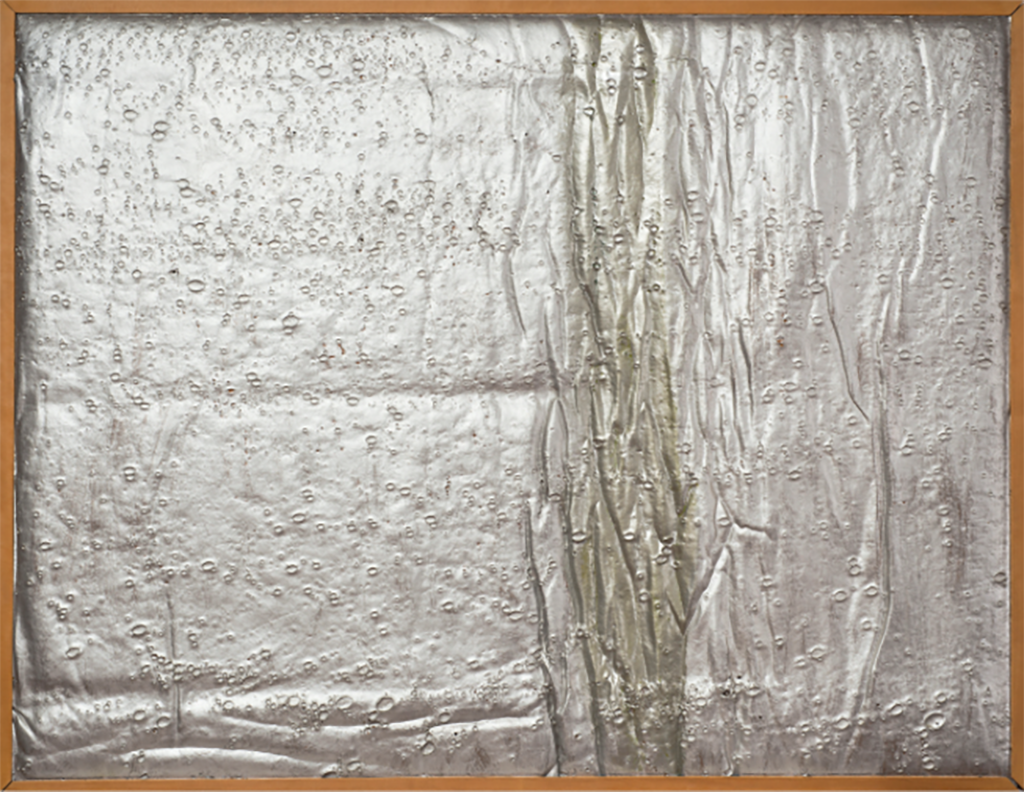

LANDING

Just a year after “2001: A Space Odyssey” opened in the cinemas, on 21 July 1969 man landed on the moon, “one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind”. The Mantuan artist Giulio Turcato (Mantua 1912 – Rome 1995) was inspired by the scientific researches that were undertaken in the 1960s, and in his works he proposed again the collective imagination of the whole decade: the race to the moon and the conquest of space. With the use of foam rubber and monochrome, from halfway through the 1960s Turcato made a series of works that recreated the surface and landscape of the moon to make tangible and real the unknown space that man was to reveal and conquer within the end of the decade. Paesaggio Lunare (1971) evokes, furthermore, the curiosity inherent in mankind, his yearning for conquest and knowledge, his perennial desire to discover the unknown, and the progressive triumph over his own limits.

[1] Il Futurismo mondiale. Conference at the Sorbonne, in “L’Impero”, Rome, 20 May 1924, as republished in the book by Mario Verdone Il Teatro Futurista, p. 9

[2] Silvio Mix e L’Angoscia delle Macchine by Stefano Bianchi, in Il Corpo del Mostro, various authors, 2002, p. 279